Year 25, Issue 4.

RE

INTER

MEDIA

TION

REINTERMEDIATION

Humans over algorithms, the movement building a new web.

Disintermediation. The idea had come from eCommerce – we’d stop buying from shops, and instead get directly from the manufacturer, farmer and tailor. It’s something the web makes easy, and without fees to the shopkeeper should make things cheaper, so seemed inevitable based on our idiot’s understanding of capitalism. But the reality of eCommerce is we mostly buy from Amazon and eBay, because few had predicted how important an easy user experience is*, especially when joined with the price-lowering power that comes from being a monopoly.

This is what I wrote giddily in the 3rd Film Finance Handbook in 2007, two years after YouTube had launched, and in between the launch of Netflix Player and iPlayer:

“So it finally happened. After over a century of cinema, the power of moving image is in the hands of anyone with so much as a camera-phone and a web connection… The web shrinks the world: for the independent artist it removes the need for a studio distribution network… [It’s] the arrival of a level playing field, which the independent producer – long forced to compete with shelf and screen space with the major studios – has until now been denied.”

I was wrong about disintermediation: terribly, devastatingly – will our kids forgive us? – levels of wrong. We weren’t wrong because we needed that bouncer, but because disintermediation actually meant something else: the Monopoly and its Algorithm.

My excuse? I’d started traipsing Soho handing out CVs to work unpaid as a runner at the fag-end of the 90s, to join a mountain of other CVs in a pile next to the bin. Tom and I had skipped our film degree after naîvely believing the guy from Enron that millions were around the corner –25 of the– two weeks before the dotcom crash. But making a website that looked as professional as any other media company’s back then helped us talk with the film industry as equals. Google ranked us #1 for ‘film funding’ and #3 for ‘film industry’ – a pair of dropouts!

I assumed the internet heralded a great age of levelling, removing the gatekeepers for a meritocratic world.

But we were the last of that generation – almost everyone who came after could only do this if they signed up to a large multinational company – YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, or Twitter. Podcasts have largely survived decentralised – boosted by protocol-integration into iTunes while Jobs was still alive – but even blogs are moving to Substack and Ghost.

The Monopoly & The Algorithm

So we swapped human curators for a profit-seeking algorithm.

We replaced the independent record store manager who knows exactly the right tune to play at this moment, the video rental clerk with the knowledge and opinions of Tarantino, the late night cult film shows, the art-house cinemas not just showing shiny Oscar-campaign films, the magazine racks at the giant bookstores where you could spend a day ploughing thru with a coffee.

We swapped them for some code owned by a company legally obliged to make as much money for shareholders as possible.

But most people didn’t notice because on social media they found ‘their people’, more than we find in traditional media – people with similar backgrounds, opinions, biases, and fears. Social media’s main innovation is built on grouping similar people, you enter a library or open a newspaper where everyone is a bit like you, and when they’re not, they’re presented as something other on a scale from funny weirdo to threat.

It’s hard for most people to see social media platform’s problems because they seem to be uniting your community – be that anti-racism campaigners or anti-refugee groups, pro or anti Brexit, pro or anti MAGA. But the algorithm depends on both these polorised groups to stay disunited and upset, to keep both groups engaged, and as is seen in study after study, ‘algorithmic radicalisation‘ pushes neutral, disinterested users towards these extremes.

These networks are now so entrenched – not just with users, but with creators: YouTube paid $70bn to 3 million creator channels from 2021-2023, a figure far higher than the $17bn the entire music industry paid musicians.

And of course – between the disinfo and hate radicalising – there’s obviously great things created and shared on these platforms, that might never have been seen in the old world of the big media bouncer.

But there’s still a bouncer, it’s just now a bot whose central instruction is ‘grow profits’.

Reintermediation: restoring a middle

What if we could bring it back?

Not the bouncer, but a place for the human curator? The specialist who can tip you 10 great albums to unwind to in the evening, or the best comedy you’ve never seen and is motivated by being good at that, rather than a giant corporation’s profit model?

Re-intermediation is the recovery of this layer at network scale. The surprising thing is there’s already millions of people developing and using a system that does this. It’s challenge is it’s still being built, so it’s often not as user-friendly, and there’s a fair chance ‘your people’ aren’t there yet. But if anything is going to bring back the best of what we’ve lost, we’re betting on this…

We live in an age of listicles – from the Sight and Sound poll to the top 25 films about eating doughnuts – yet the web never built a standardised curation layer. So unfriendly are the various gated monopolies towards each other that despite sharing an HTML foundation that was designed to connect everything everywhere – there’s not even a curation-layer monopoly. ‘The internet has devolved into screenshots of screenshots of other social media sites’ (ref) because it’s the only way we can bridge these gated monopolies.

The closest are DJ-sites like Mixcloud and review sites like GoodReads and Letterboxd. But both of these exist outside of your other media and networks: I can’t buy a song I like in a Mixcloud session; GoodReads links me to bookshops and libraries but my reviews there can’t also sit on my blog or LinkedIn. They’re inside the gate.

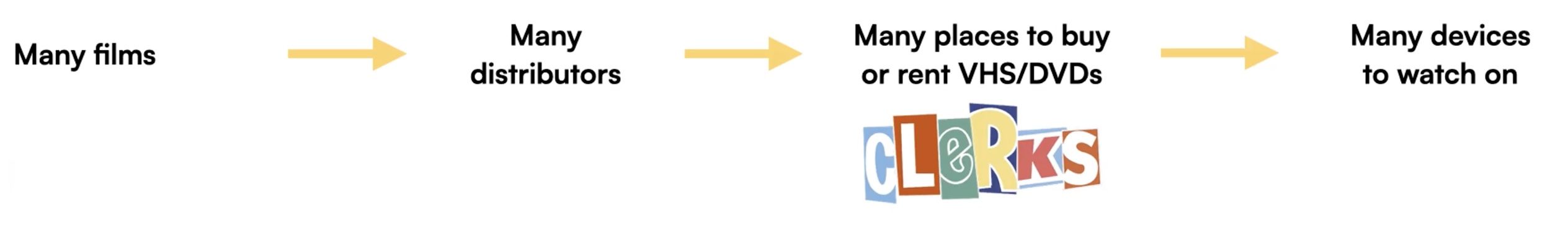

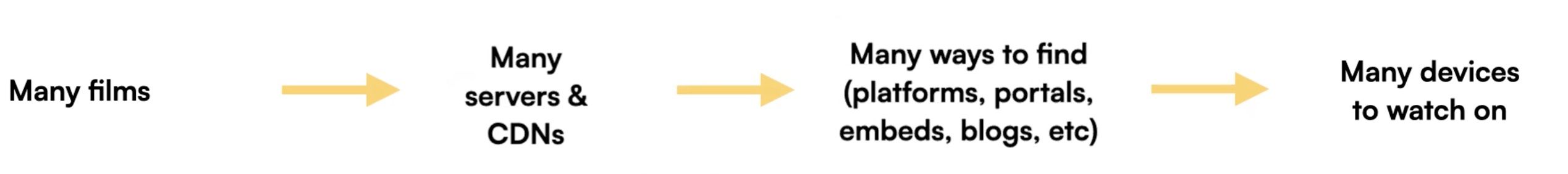

A real curatorial layer needs to be at a distance from both the source of the media and the player its outputted on. It’s as simple as a video store being a different entity to the video player in your house and the distributors and studio’s who’s films are in the store. We’d never consider going to a video store that only shopped films from one distributor or that only played on one brand of VHS player – yet that’s exactly the web we’ve ended up with.

VHS/DVD distribution was really competitive at four levels…

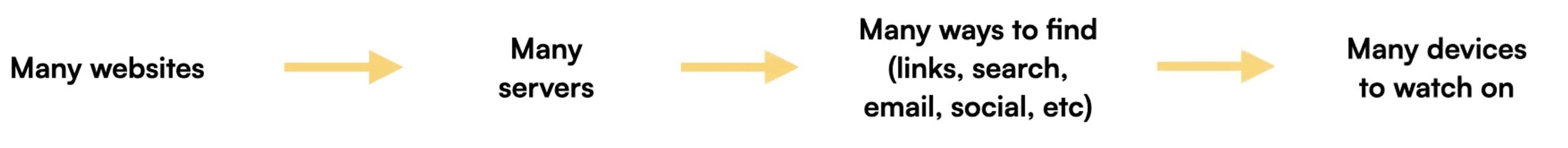

It’s quite similar to the web’s design…

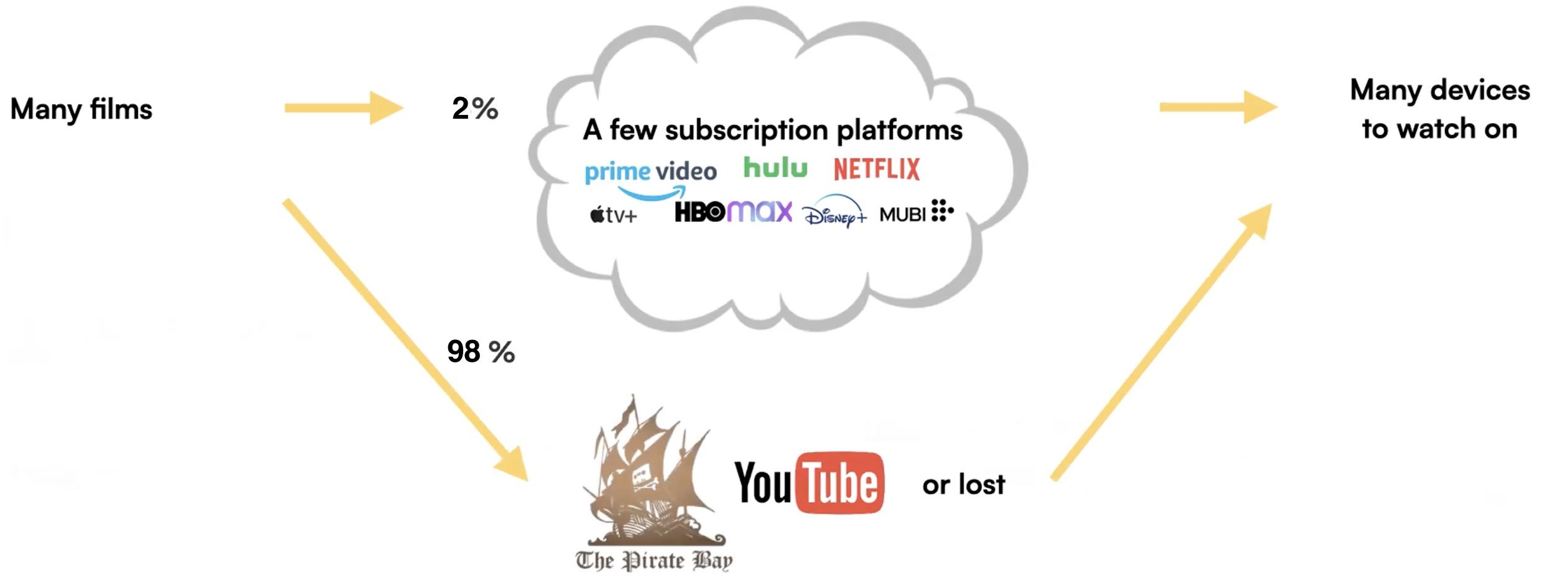

But somehow we’ve ended up with this…

We’re so used to end-to-end gated media it’s hard to imagine any different. Re-intermediation is built on restoration of this separation through common standards – and restoring a curatorial layer is only one of the advantages.

A protocol-led film ecosystem that separates distributor, platform and player also supports an architecture where you don’t need to keep logging in and out of different subscription services to see media owned by different platforms – you just have your choice of player which works seamlessly with all of them. And best of all, because the player isn’t tied to one platform, the hundreds of thousands of films that aren’t on these platforms can be found…

The craziest thing about how film is distributed online is 98% of films aren’t available legally…

1,115,944

70,000

12,828

20,774

source ReelGood, Finder

So the web distribution architecture is really…

Reintermediation is about splitting that middle step in two again.

Where the indie video shop was built on the VHS standard, and the indie record store was built on CD and vinyl standards – the reintermediated web is built on protocols and follows the same four steps of 20C media distribution and the web’s foundational architecture.

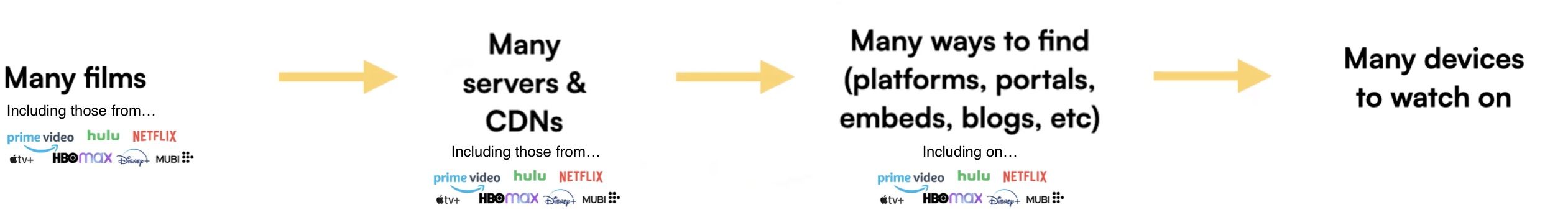

So the idea is to ditch the platforms that invest billions in production?

Not at all. The idea is just that they compete at each level, just as a Universal film, would show in a Warner Village cinema, and at a Blockbuster (same owners as Paramount) video store, broadcast on Disney’s ABC channel to a Sony TV. Every step of 20C media distribution had a level of competition, and this allowed for a viable and sometimes thriving independent film scene alongside the studios. So the idea is something more like this…

Here a Disney film might be stored on an Amazon streaming server, and play through my Netflix subscription onto my Apple TV.

At the heart of this is the idea of rights-holders tagging each of their works with a minimum price for renting, owning and streaming their film in different countries, which platforms can then re-offer to their users and subscribers.

Currently, for most rights owners Amazon Prime only pays around 1 cent per feature film play; with this model a rights-owner might say ‘our film needs a minimum 1 cent for each 10 minutes played of the film’ and only the platforms that meet that requirement can stream it – potentially even those without subscription fees who can meet that license fee via advertising (unless the rightsholder stipulates ‘no ads’).

Filmmakers get their work on all platforms without doing deals with each, and platforms have access to a far larger pool of titles. And viewers can choose the platforms and players that either have the best price, the best curation and discovery, the interface they find easiest or the community where their friends hangout and chat on.

The Fediverse

For over a decade, a monopoly-proof reintermediation layer has been under construction by developers and community builders across the world. It’s not yet finished, but this so-called ‘Fediverse’ of decentralised-but-connected media networks is a facsimile of the old media separation:

- Creation: creators create and host their work on *instances*.

- Distribution: other *instances* boost and promote this content into other networks.

- Playback: *Apps* help people subscribe to and engage with this content.

Some instance apps best for hosting video, photos, podcasts, music, etc, while others are best for making networks, bookmarking, sharing and chatting. Different companies, non-profits, coops and volunteer groups are involved in all of these steps making and managing an entire ecosystem of compatible services.

Don’t feel bad if you haven’t heard about it. As something that’s trying to be monopoly-proof and is driven mostly by unpaid developers, EU grant-funding and non-profits, it doesn’t employ a publicity team. Instead it’s mostly just tech people explaining all this. And tech people often describe protocols in terms of functions and capabilities, rather than the cultural impact and potential.

I hadn’t really understood it until 2022. I’d had an account on Mastodon for five years, which adopted ActivityPub in 2017, trying out a cooperative-run instance that I pay $1 a month to support paid moderators. I found I had a much nicer experience chatting with my 18 or so followers than I had on Twitter with 2,600 followers. But then in 2022 I installed PeerTube – the ActivityPub video platform – on a server in about five minutes and had an oh-this-changes-everything moment.

I’ve been trying out free and open video hosting apps for as long as the web’s been releasing them – and mostly it’s a headache to setup (the server needs to be able to handle and transcode large files, and stream them smoothly). But this was so easy to setup and use but also instantly offered something YouTube doesn’t – it could federate with other instances. Together this could make an algorithm-free space where creators could define the terms of engagement. I instantly rewrote the $100k project Netribution had been funded by the Interledger Foundation to deliver. We had to focus on this potential.

Before I explain how we did that, let me rewind a second as I need to emphasise something significant: the protocol ActivityPub powers the Twitter-ish Mastodon AND the YouTube-ish PeerTube. This isn’t the same as saying they both use the same programming language (they don’t). It’s like being able to subscribe to YouTube channels from inside Instagram, and a comment on my Instagram app shows up on the YouTube. Rather than a walled garden, ActivityPub is a network of parks.

For all of us dreaming of a world where you could watch a ‘syndicated’ Disney Plus or Apple TV show via your Netflix subscription – alongside 1000s of obscure archive and non-English films that are hard to find anywhere – this is curious heart of the Fediverse. Its goal is a web where you could bookmark your Instagram faves on your TikTok app, ReTweet your YouTube video to Facebook, buy your Spotify playlist in iTunes – while a humble blogger (or indie band or filmmaker) has instant publishing across all these spaces. It sounds crazy but it’s not really any more complex a business model than playing CDs in your DVD player. It’s a borderless social web and that’s both amazing and scary at the same time.

Introducing some of the bigger Fediverse networks…

Loops

Short form video network from the creator of Pixelfed.

Peertube

Over 600,000 videos are hosted over 1,000+ Peertube instances.

Where this gets really confusing for newcomers is all of these, other than Threads, are open source applications – and while many have their own official community (e.g. Mastodon has mastodon.social, Pixelfed has pixelfed.social) – most people sign-up with other servers hosting ‘instances’ of these apps.

But this doesn’t matter to the wider ecosystem. A Mastodon user on a Mastodon Android app can follow and engage with any user on any Mastodon instance, if it’s not been blocked by their instance moderator, which is how moderation is handled. They can also follow PeerTube, PixelFed, Bonfire, Lemmy, Ghost, WordPress and Threads users. The interactions available vary with client and server app – but the principle is simple – use ActivityPub to support interactions between actors and objects across different servers and apps.

At the centre sits ActivityPub, a protocol that describes how people (‘actors’) can create and interact (‘activities’) with content (‘objects’) regardless of where they are. Different open source server applications such as PeerTube for video and PixelFed for images are hosted as instances by different groups. Users of each can follow each other – unless they’ve been blocked either at user or instance level. So there are white supremacist / X-like Mastodon instances, the instances listed above block them through a shared block list. The final step are the client apps that let users interact with their instances from their phones and desktop.

But what of BlueSky? And the rest?

Tho ActivityPub powers this WordPress site, it isn’t the only open protocol for decentralised media. Far older is RSS, which still powers most Podcasting, while two other protocols have growing ecosystems followings (IMAP/Matrix/Signal are similar but more for messaging).

In a VHS vs Betamax type protocol-split we focus on ActivityPub as it’s a W3C standard and seems less centralised. It also has bridges with both: Ditto for Nostr and BridgyFed for AtProto; apps like OpenVibe work with all 3.

AtProto

AtProto was backed by Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey after analysing the limitations of ActivityPub. It’s got some advantages, while the BlueSky app is polished with lots of features (tho no edit button), and millions of X-iles who decamped from Twitter. Rudy Fraser’s BlackSky is an independent black-community focussed AtProto project seeking autonomy from BlueSky, doing impressive work.

Nostr

Another Jack Dorsey-backed project after he felt BlueSky too centralised. Nostr is an open protocol with privately owned ‘Relays’ – the re-intermediation layer. Its big USP is it claims to be censorship-proof, plus every piece of content is ‘signed’ making it impossible for a relay to change it and integration of tiny Bitcoin payments (‘zaps’). Growth outside of crypto-circles hasn’t happened yet.

There are more users of ActivityPub enabled apps than there were web users when Netribution launched in 1999*.

*but almost all of them are on Threads

Slow down and get it right…

We’ve been led to believe that if something isn’t an overnight success then it’s not worth bothering with. Today’s web monopolies enjoyed stratospheric growth when they arrived. Meta’s ActivityPub-aligned Threads shot to over 100 million users quicker than any app before (5 days), and in under two years has overtaken Twitter/X for active daily users. It’s bigger than the web was when Netribution launched. But the monopoly-free Mastodon hovers around a million daily active users out of 12 million or so accounts. Those million-or-so users have been static for a while, as, arguably are the communities on BlueSky and Nostr.

Some on the Fediverse are happy with this – a mountain village few wish to visit that works for its residents much more than Twitter ever did. But others want it to offer an alternative to the digital web monopolies, which means both being able to scale up moderation, and participate in the creative economies which provide incomes for millions of creators on the giant platforms.

The reality is it can be both. Federation allows mountain communities to keep protecting themselves, or build a high-speed train station (/ space port). The protocol lets each community choose the type of village they want to be, and this often varies depending on what media is the focus. If it’s music or cinema many would want the biggest library of songs and films possible; if it’s news it’s a bit larger (but not too large); if it’s opinions or blogs or social video many people want something smaller, that’s probably unique to them.

The question of how the creative industries – musicians, filmmakers, photographers, artists and writers – could make money on the Fediverse was the heart of Monetising Open Video Architecture (MOVA), the large project Netribution led in 2021-22.

At the heart of this is the idea of subscriptions that travel with you as you browse the web and move between apps; while the media you buy online is stored independently of any cloud platform or proprietary system. It’s yours for life, just like owning a printed book, record or DVD.

The reintermediation part is the added-benefit of allowing the human who recommends you that work of culture – DJ, librarian, film programmer or art curator – sharing some of the revenue. It sees a shift from an algorithmic intermediary for a smallish number of films on multiple competing services, to humans helping humans discover culture from a far bigger ocean of media.

This is what we looked at in 2022, and centres on a few separate concepts…

Lists, lots of lists

Christine Columbus uploads a Harry Potter film. Am I sure they’re the owner of the film as I stream them micropayments from my Fantasy Film Subscription? What if I want to find other wizard films? What if I’m 12 years old and want to watch Mr Wizard’s Wand without realising it’s adult content – bringing my platform owner into legal jeopardy – and exposing me to something certified 18?

At the moment there’s no platform-independent architecture for creating lists of content with specific information attached. Some exist around CSEAI/CSAM – PhotoDNA is a Microsoft-operated list of CSEAI images – to help platform moderators report and block the worst kind of video and photos. Mastodon has lists of servers who meet the community governance proposals and servers who’ve been blocked. IMDB and TMDB have metadata on millions of films; OMDB and MusicBrainz has data on millions of tracks; DOI has metadata on millions of academic articles.

We built our own protoype – MOVA – to fingerprint videos using a new algorithim called the ISCC, then attach ownership, license and other verifiable metadata to the fingerprint. We tried to make it as decentralised and open as possible using another new system called Holochain, a process which helped clarify the scale of the challenge for doing this with video in a legally and morally sound way.

A simple example: one person makes a list of LGBT-friendly films; in Russia they’re illegal, in Afghanistan watching them can sentence you to death. Lists can add functionality, but they can also facilitate corporate and and state censorship –and worse– when combined with fingerprinting. The European Commission are funding something similar to MOVA – CommonsDB – to help flag unlawful takedowns of public domain world, and potentially block AI training model use.

There’s potentially an infinite number of possible lists. From our perspective, the minimum required list is to be able to reliably verify that payments for a piece of media are going to the right person or legal entity. Who has the right to earn from it?

We developed three projects using and inspired by these ideas:

Netribution’s history starts with arriving too early – our first website was designed to be a place to watch films, but most web users then had dial-up modems and struggled to get large photos to load on the screens, let alone movies. With Netribution 2.0 we were in sync – with our “Imagine a newspaper written by its readers” document coming ahead of the rise of social media. These two experiences give two different reasons for caution: having the right idea at the wrong time; and having an incomplete idea at the right time.

The technology for a different kind of web has been built, but the systems within it to scale and provide an income for creators and moderators hasn’t yet. Furthermore, the tools to scale community-led decision-making as the number of users scales isn’t there yet. A different kind of web media can’t just be the powerhouse for the techies who know how to navigate a code environment to change things. As a result I’m not presenting this as something happening right now that will arrive in the next six months; I’ve been saying for a while it will take the rest of the decade. There’s also a chance it doesn’t happen at all.

Google’s biggest selling point when it first arrived was that most of it’s home page was white. It just had a logo and a search-bar and two buttons (search and ‘I’m feeling lucky’) plus a tally of how many pages indexed, at a time of over-cluttered website. There weren’t even ads on the results back them (how will they fund themselves? we foolishly pondered).

Facebook introduced Ajax, a technique that let you update just a small part of the page after interacting with it, rather than re-loading the whole thing. Before them clicking a ‘like’ button reloaded the entire page to update the count of likes – Facebook reloaded only the count – a tiny barely perciptable thing that made it nicer to use than MySpace.

iPhone introduced pinch and zoom for web browsing. Twitter forced people to write succinctly. Instagram solved the problem of aligning landscape and portrait photos on a feed by forcing square pics on everyone, which work just as well whether you’re on a portrait phone screen or landscape desktop computer. TikTok kept videos short and in the same portrait mode people hold their phones.

Each of these platforms did something that made life easier for users. And that’s probably why many people are going wild over AI – not because it reliably produces better quality work, but because it’s so much easier to use than us humans.

Let’s take it to the bridge…

Netribution 1 launched at the end of Web 1. Netribution 2 launched right in the middle of Web 2.0. This year of issues to celebrate Netriibution’s 25 years is coming ahead of a Web of Third Kind that, I think, seems inevitable.

It just might be a few more years away yet. Or I might be wrong and the monopolies face neither state nor market incentive to do anything differently – no ‘killer’ Fediverse app emerges, and users keep doom-stroking exactly where they currently are.

But maybe not. So we wanted to let you know, faithful reader who’s got to the end of this, where we think things are heading.